Good day my good friend.

Ask not what your newsletter could do for you, but what you can do for your newsletter, is probably something John F. Kennedy would ask if he was writing this. But he isn’t, so it’s me instead.

The main way by which I grow my subscriber numbers is not through social media, but through recommendations from you. If you like the content of my newsletter, I humbly ask that you forward it on to four or five others. And if you have had this forwarded on to you, please subscribe (its free and I don’t SPAM your inbox). It all helps a lot, and certainly keeps me motivated to write more.

Anyhow, onto the newsletter.

💰 Where we spend the dough

Every year, the Office for National Statistics publishes an extremely interesting dataset called Family Spending in the UK. This is data on how much the average family spends each week, on everything from bread to nights out, via the mortgage or rent. Needless to say that details of transport spend are also provided, and they provide a fascinating insight into how we spend our money on how we get around.

Lets start with some basics. In 2024 (the latest year for which there is data). The average British family spends £88.20 per week on transport. Of this, £31.20 is spent on the purchase of vehicles (e.g. financing or outright buying them), £33.50 is spent on their “operation” (e.g. fuel, repairs, and parking), and £23.40 is spent on transport services.

This latter one is really interesting as you dig into the data. What it shows is that, rather than spending lots of money on public transport fares, the average family spends their money on air travel and car leasing. In fact, the average British family spends double the amount per week on international air fares (£10) than they do on rail and bus fares combined (£4.80).

Spend on transport services by the average British family each week (Source: ONS)

This might sound shocking to many, but a glance at the National Travel Survey data gives some insight on why this is so. In terms of how frequently most people use different modes of transport, for rail, buses, and planes (in fact for every mode of transport other than the private car or walking), the most cited frequency of how often people use these modes is Less than once a year or never. This is the case for 50% of respondents when it comes to local buses, 88% for non-local buses, 95% for air travel (domestic - international flights are not counted in the NTS), and 41% for surface rail. In short, most people never use public transport, and if they do fly chances are the ticket will be relatively expensive - especially if flying with a family.

When it is broken down by income group, there is no shock that those in higher income households spend much more on transport. Households in the top income decile spend nearly £200 a week on transport, over twice the average household spend. Here there are some interesting quirks. For instance, the highest income quintile group spends more as a percentage of their weekly spend on used cars than each of the lowest seven income decile groups (29% of transport spend, compared to an average of 24% for the seven lowest groups). The highest income quintile group also spends more on public transport fares as a percentage of their transport spend than the lowest income quintile group (7% compared to 6%), likely due to their increased likelihood of using trains. I do like to quote my favourite insight from the NTS that the poorer you are the more likely you are to use a bus, while the richer you are the more likely you are to use a train.

Spend on transport per week in the UK per income decile (2024) (Source: ONS)

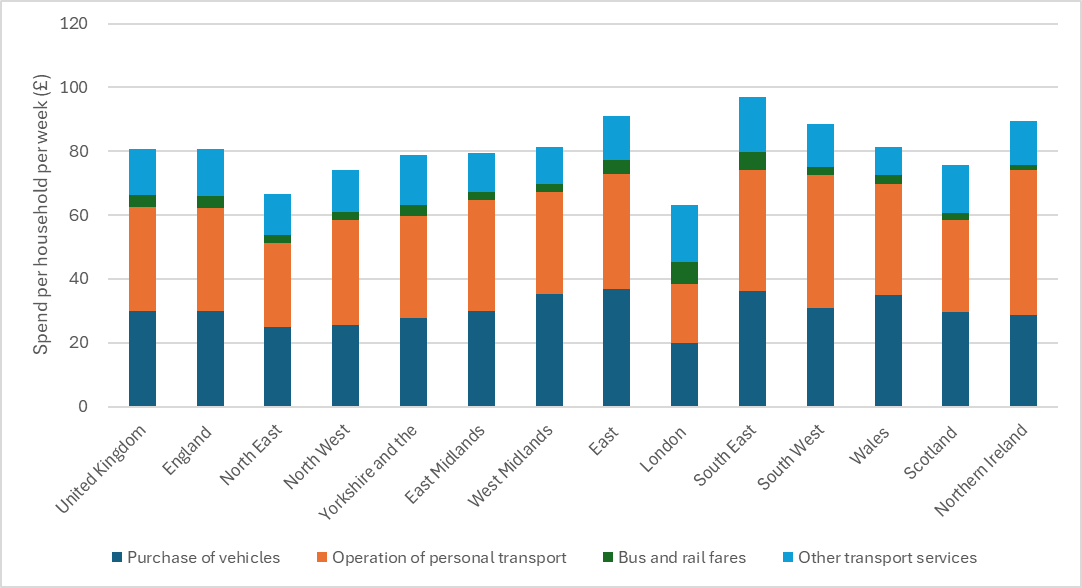

There are also significant, and sometimes surprising, variations by region. Despite the loud complaints I often get from London friends, they actually spend the least per week on transport (£63.20). In large part because they spend less than other regions on both purchase and operation of vehicles. Not a shock considering that the data shows that 33% of households in Outer London do not own a car, rising to 62% in Inner London. The highest spending region overall is the South East at £97.20 per week. Driven mainly by higher amounts paid on purchasing and operating vehicles, but also only being second to London in terms of spend on public transport. Likely driven by London’s extensive rail commuter market.

Spend per week per household on average by region (£) (Source: ONS)

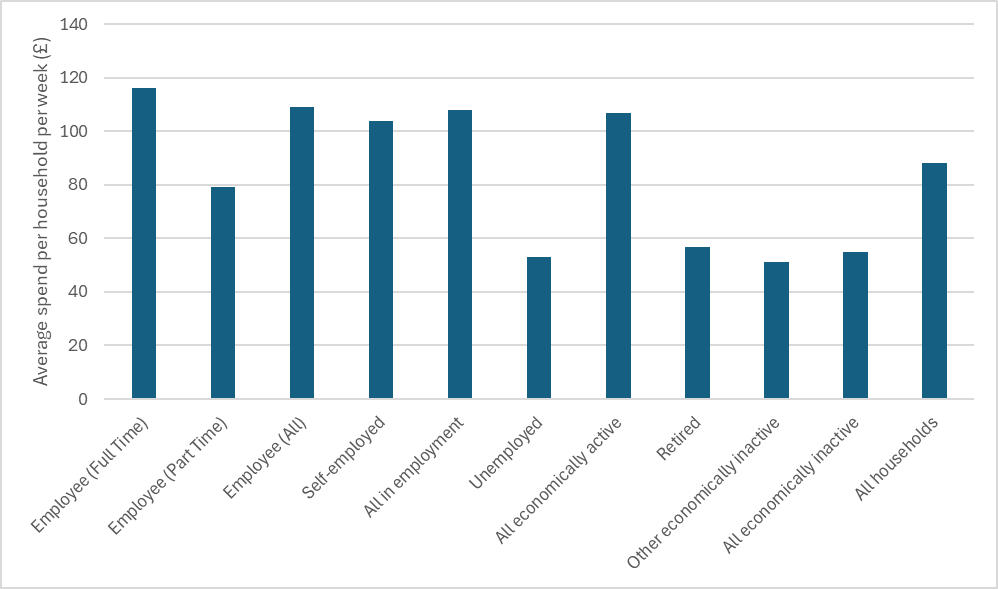

A further really interesting finding is how different household types spend on transport differently. This is partly achieved in the data through understanding the employment status of the Household Reference Person. Think of this as the historic “head of the family.” People who are economically active, on average, spend more per week on transport - £106.70 per week, though this substantially reduces for those who are unemployed and working part time. For economically inactive households, this spend nearly halves to £55 per week. As well as the obvious factor of lower incomes restricting spending, it should be noted that economically inactive groups includes the retired and students, who often benefit for substantial public transport discounts or free travel.

Average spend on transport per week by employment status of household reference person (£) (Source: ONS)

Finally, it is impossible to not look at this over time and how things have changed. Believe it or not, while the absolute number has risen, once you factor in inflation, the average British household is spending less each week on transport than it has at any point in the last 20 years, except for the COVID-19 pandemic. While it is £88.20 per week in 2024, adjusted for inflation it was £116.20 in 2001/02. Incidentally, if you are after the percentage of total weekly spend on transport services, in 2001/02 it was 16%. In 2024, it was 13%. A figure that has been remarkably consistent over the years.

Average spend per household on transport each week - inflation adjusted (Source: ONS)

I have put all of this data here because there are common narratives around links between income and how people use transport based on the National Travel Survey. Such as the poorest in society tend to use buses more (they do), and the richest fly more (they do). But these observations on behaviours do not translate necessarily into expenditure in the economy.

What strikes out to me from this data is a few things. The first is that a few big transport items matter a lot. Buying and running a car and getting that one return international flight a year really makes a dent in the family finances, and while the latter can be seen as a luxury, the former is essential to living everyday life for most people. Giving up a car could represent a major saving - as indicated by lower overall transport spend per household in London - but it also could affect people’s ability to have a sufficient income.

While I mention the regional data, what is amazing is how spending on transport is high south of an axis running from the Bristol Channel to The Wash, taking in the regions of London, the South East, East of England, and the South West. London, the South East, and East of England I can probably explain by close proximity to the capital and greater relative economic prosperity, but the South West I cannot fully explain. It could possibly be due to longer distances needed to travel to major urban areas, particularly for areas of Dorset, Somerset, and the northern parts of Devon and Cornwall. But I do not know. I should also state that Northern Ireland is a similar outlier, again for reasons I do not know.

A further interesting thing is how much used cars drive expenditure. It is tempting to think that the higher income groups buying Jensen Interceptor’s and old Ferrari’s constitutes their spending, but I am not so sure. I think this group may purchase more than their fair share of used Audi’s and Fiat 500’s for their children. But across the groups, this data really strikes home to me quite how important used cars are to mobility across the country. Maybe if we are to crack decarbonisation, electrifying the used vehicle fleet is key to achieving this.

Finally, we often think of affordability in terms of public transport fares, and equitable solutions for those on the lowest incomes. And that is part of it. But a big part of it is understanding how people spend money on transport now. As this data shows, this is a complex picture, taking account of income levels, household composition, and where people live. Fare policy is a blunt instrument that is within the control of transport professionals - the same with demand management. But in terms of how people spend, a fare policy on a mode of transport they rarely use is nice, but does not matter as much as things like cutting fuel duty - however correct that policy may be.

👩🎓From Academia

The clever clogs at our universities have published the following excellent research. Where you are unable to access the research, email the author – they may give you a copy of the research paper for free.

TL:DR - Introduces and compares three structural concepts (differential, integral, hybrid) for a low‑floor rail vehicle body, analysing manufacturability, stiffness and passenger comfort to support more efficient and accessible regional rail vehicles.

TL:DR - Assesses how various land‑use transitions over a decade in Melbourne influence subsequent crash frequencies, demonstrating that changes introducing higher activity and vulnerable road users raise long‑term road‑safety risks.

TL:DR - Proposes a deep‑learning model tailored for route choice in scheduled public‑transport networks, outperforming traditional Path‑Size‑Logit models by capturing nonlinear interactions (e.g., weather, socio‑demographics) and improving choice prediction and interpretability.

TL:DR - Via a driving simulator experiment and microsimulation, investigates how human‑driven vehicles adapt their behaviour due to automated vehicle penetration and driving style—highlighting important traffic modelling and policy implications during the transition to mixed fleets.

TL:DR - Introduces “MobilityGen”, a deep‐generative model producing realistic multi‑day mobility trajectories at large scale, capturing location visits, mode choices and co‑presence dynamics — enabling fine‑grained simulation of mobility behaviour and its social and spatial implications.

😀Positive News

Here are some articles showing that, despite the state of the world, good stuff is still happening in sustainable transport. So get your fix of positivity here.

A new off‑road cycleway and footpath linking South Ribble with Preston Railway Station has officially opened, connecting into the Guild Wheel route and improving access to the city centre and station.

Construction has begun on the first of an additional 10 new trains for the Elizabeth line, responding to growth in demand and enabling more frequent, reliable electric rail services.

The new £175m station on the Great Eastern Main Line has opened ahead of schedule, unlocking thousands of new homes, creating jobs, and improving sustainable transport access.

Outlines how mobility innovations including cloud/AI are being deployed to tackle transport challenges and foster efficient, safe, sustainable travel.

Carmarthenshire County Council opened two brand-new off-road walking, wheeling and cycling sections on the Tywi Valley Path, progressing the 16.7-mile traffic-free route that will link communities from Llandeilo towards Carmarthen. Further segments are due in November, with the project connecting to heritage sites and the Heart of Wales rail line to encourage car-free trips.

📺On the (You)Tube

Hot on the hells of the news earlier in this newsletter that Beaulieu Park station in Chelmsford is now open, Geoff Marshall paid a visit to it.

📖 Bed Time Reading

This last week I have spent my time reading a somewhat controversial urban planning books from the 1980s: Utopia on Trial by Alice Coleman. In this book, the author reports on the work of her research team at King’s College London on aspects of planned estates (namely tower blocks) in British urban planning, and how they have failed socially.

The evidence presented is damning. Certain design features are shown to correlate with things such as the presence of litter and vandalism. It recommended numerous design changes, such as removing elevated walkways and installing private gardens in shared areas on the ground floor. It also praised inter-war suburban housing as having good design features from the perspective of reducing anti-social behaviour.

But what made it controversial was how it influenced the housing policy of the Thatcher government - namely that these were failed estates that needed substantial regeneration. Academics and civil servants at the time absolutely hated Coleman’s findings. I highly recommend reading Peter Dicken’s critique of Coleman’s work, especially as she dismisses the link between poverty and the presence of many of the anti-social behaviours she lists.

📚Random Things

These links are meant to make you think about the things that affect our world in transport, and not just think about transport itself. I hope that you enjoy them.

An Optimistic Quest in Apocalyptic Times (The Bitter Southerner)

Why AI Breaks Bad (Wired)

The Invention of the Traditional System of Project Delivery (Pedestrian Observations)

🎶 Musical Out-Tro

A year ago, Linkin Park made a big comeback just over 7 years after the death of their frontman Chester Bennington. Now, with a new leading lady in Emily Armstrong, the Emptiness Machine has been ringing in my ears for the better part of a year. Enjoy.